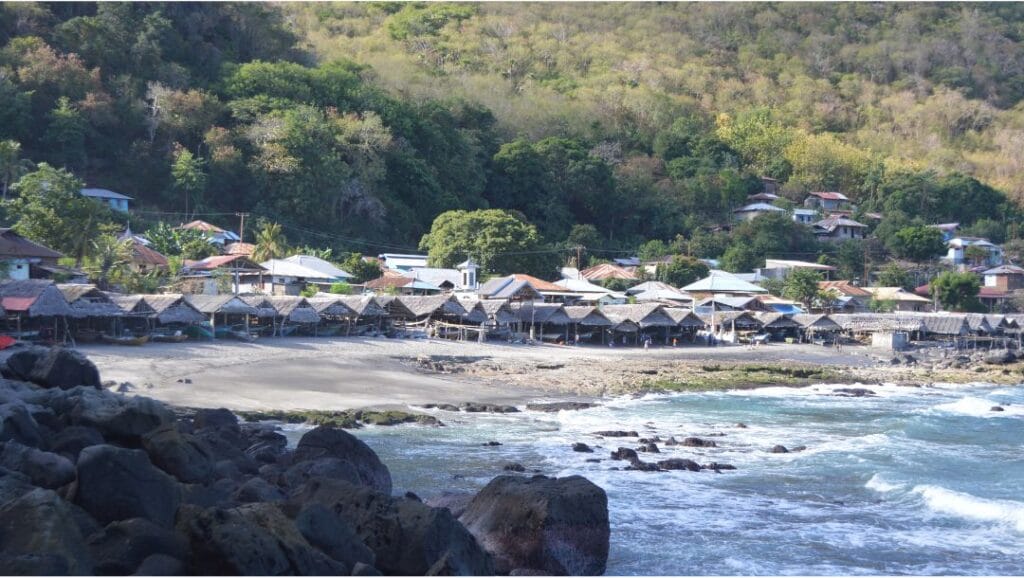

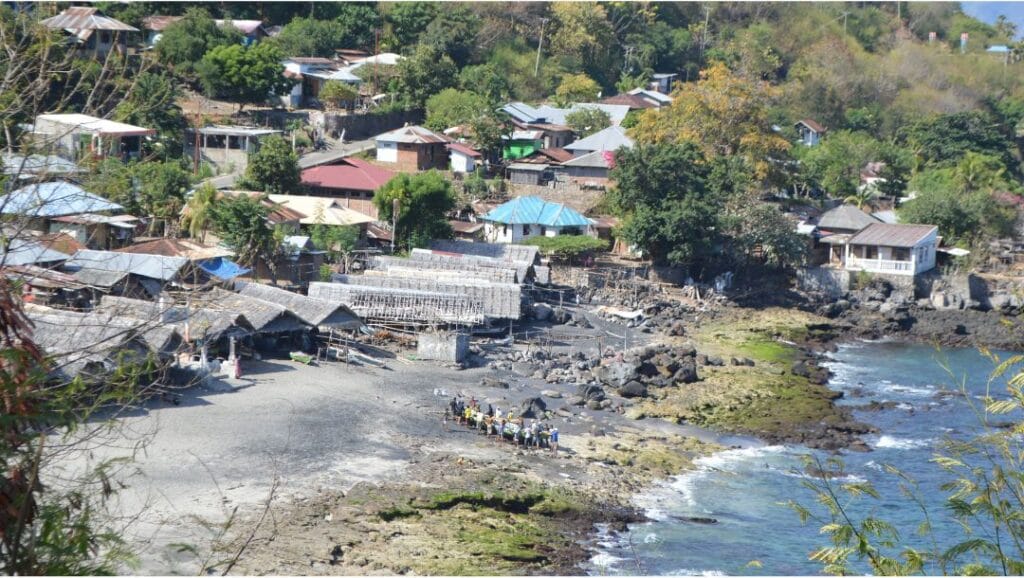

For hundreds of years, the men, women and children of Lamalera, a remote fishing village nestled on a rocky hillside at the foot of a volcano in far eastern Indonesia, have scanned the sea for the unmistakable spray of a blowhole on the horizon. When one is spotted, the shout will sound out: ‘Baleo!’ and the men rush to get the peledang, slender wooden boats, from their boatsheds on the beach and carry them down to the dark churn of the Savu Sea. The chief hunter, the lamafa, will take his place at the stern, and ready his harpoon in the hope of catching the most prized beast of the sea in centuries gone by: the whale.

Lamalera feels a million miles away from Bali, where spirituality is commodified and repackaged for the right price and ancient forests and rice fields are paved over for gated communities built with crypto fortunes.

Yet today the whale hunt faces pressures from all angles. Conservationists and animal welfare campaigners have been trying to stop the hunt for years. Lamalera slips through the net of the ban on international commercial whaling: Indonesia is not a signatory of the International Whaling Convention, and if it was, Lamalera’s hunt would be permitted as an indigenous subsistence practice. The campaign to end the whale and dolphin hunt may evoke strong emotions through its imagery of dead orcas on Lamalera beach, but what would happen to the village if its indigenous hunting practices were banned? Would its fishermen move to lucrative jobs in the commercial fishing industry that is draining the seas around Indonesia of its natural biodiversity? Would it follow the example of Lovina, Bali, in offering whale and dolphin watching for tourists, with the resulting incentives to crowd and stress the sea mammals in the search for the best dolphin selfies? Or, faced with the realities of a warming ocean and a changing climate, could the village offer a priceless alternative to commercial overfishing and over-tourism: a spiritual and sustainable relationship with the land and sea?

A village with no restaurants or cafes and limited electricity, still hunting at sea with wooden boats and bamboo harpoons, Lamalera feels a million miles away from Bali, where spirituality is commodified and repackaged for the right price and ancient forests and rice fields are paved over for gated communities built with crypto fortunes. Bali may offer a vision of Lamalera’s future if outsiders were to succeed in replacing traditional indigenous practices with a market economy that is dependent on tourist spending and where farmers face huge pressure to sell their rice fields to hotel developers from off the island.

Here in Lamalera electricity only arrived in recent decades and the whale and dolphin meat is not sold for money, but their way of life is still under threat from the realities of the Anthropocene: heating oceans and pressures to modernise.

The whale and the whale hunt are central to the spiritual and cultural identity of the village. The villagers believe their ancestors, who migrated to Lembata island from Sulawesi hundreds of years ago, were saved from drowning by a blue whale, and the blue whale remains protected from the hunt. The lamafa has a very important role. It is not just a hunting role, it is a spiritual role. The whole hunt is very spiritual,’ local guide Antony Lebuan tells me.

“Would Lamalera follow the example of Lovina, Bali in offering whale and dolphin watching for tourists, with the resulting incentives to crowd and stress the sea mammals in the search for the best dolphin selfies?”

‘The season starts only after making offerings to the gods, to the ancestors, and going to church and praying. And once the whaling season has begun, he must behave in a sacred way. He can’t have any conflict with other men in the village because it would mean the hunt was no longer pure.’

‘And, in the season, you know, he cannot make love with his wife,’ Antony says with a twinkling grin. ‘See what a serious thing this is!’

‘Don’t mention conservation’

‘Whatever you do, don’t mention conservation,’ Antony tells me before I arrive in the village, tipping me off to the village’s complicated relationship with outsiders.

In the early 2000s, efforts to create a protected marine area across the Savu Sea led to tensions with villagers. The WWF and The Nature Conservancy (TNC) sought to establish relationships with Lamalera through a photography project, but kept their aim to end the whale hunt a secret. When the conservation agenda was exposed, the NGOs were expelled from Lamalera.

Confusingly for the villagers, earlier outside interventions aimed at increasing the village’s catch. In the early 70s, the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organisation attempted to modernise Lamalera hunting practices by introducing petrol-powered boats and synthetic gill nets. The resulting use of motorboats instead of the traditional peledang became a focus of environmentalist campaigning that paints the whale hunt of Lamalera as mechanised, modern and commercially driven rather than an indigenous subsistence hunt.

“The village’s indigenous hunting contrasts sharply with commercial industrial fishing which scrapes the ocean floor of its protein one species after another until near depletion, packaging the catch into frozen fish fingers and face products.”

In the face of this outside pressure to change, the villagers are protective of their right to hunt whales and other mammals. Local guide Poly Beker tells me that the villagers are forced to hunt at sea to feed their families. There is a saying in the Lamaholot local dialect: na plau pe me tite (the sea below is our garden).

‘There is nothing on the land. The villager’s livelihood is in the sea, catching whales, dolphins, manta rays, flying fish and other fish. The land is barren and full of rocks. It promises nothing.’

There are other traditional protections of the marine resources, including restrictions on catching pregnant or nursing mother sperm whales (although a sperm whale fetus on display in the village indicates this may not always have been followed). While imperfect, the village’s indigenous conservation contrasts sharply with commercial industrial fishing which scrapes the ocean floor of its protein one species after another until near depletion, like the orange roughy that is packaged into frozen fish fingers and face products as a ‘natural’ ingredient, known for its soothing effects on skin. In a desperate race to the bottom, trawlers south of Tasmania scooped up so much orange roughy fish on St Helen’s Hill seamount that processing plants could not keep up and tonnes of fish were dumped into landfill.

Meanwhile, in Lamalera the day’s dolphin meat is distributed across the village so that all receive a share, from the families of fishermen and boat builders to elders and widows. The women of the village cut and prepare the meat, bones and oil, drying strips in the sun outside their houses, then place it on their heads and walk up the hill to the barter market every Thursday and Sunday, where they exchange it for vegetables, rice and pinang (betel nut) from Lembata island’s mountain villages.

Lamalera’s hunt is small compared to the commercially driven whaling industries of Japan, Iceland and Norway. The village caught 120 dolphins and one whale in 2024, and none was sold commercially. Japan’s government-subsidised industry catches a few hundred whales each year and around 500 dolphins, undershooting the government quotas because of declining numbers. The Japanese determination to continue hunting whales and dolphins is strong, with the industry trying to find new ways to market whale meat despite falling consumer demand. Most of Iceland and Norway’s whale meat is exported to Japan as demand in these countries is low.

“The whole hunt is very spiritual. Once the whaling season has begun, the hunter must behave in a sacred way. He can’t have any conflict with other men in the village because it would mean the hunt was no longer pure.”

Where have the whales gone?

Yet one thing the village has in common with the commercial whaling countries is that they are all finding fewer and fewer whales in the sea. Poly Beker tells me that only one whale has been caught in 2024, while the village requires three whales per season to provide enough food for the population.

‘No one knows why the whale numbers decrease each year, even the elders. They will have to sit down and have a ritual over it.’

Ocean heating, acidification, marine heatwaves, pollution or commercial shipping could all be responsible for the changing migration patterns of whales in the Savu Sea. The choices faced by the village are stark.

‘They will change to offering whale watching and diving,’ Anthony tells me.

Should the village bow to the commercial pressures of the tourist dollar and the incentives that go along with it? For the animal welfare campaigners, this would signal an end to sea mammal bloodshed in the village, but is the vision offered by Bali’s desperate scramble for tourist cash any more ethical? The calls of ‘baleo’ on the sight of a whale may soon be a thing of the past in Lamalera, but the village, clinging to the rocky slope beneath the volcano on the edge of the Savu Sea, may be facing a precarious future.

From the author:

I am a freelance writer based in Indonesia. My work can be found at www.susannahosullivan.org and IG @usedtobecool8.